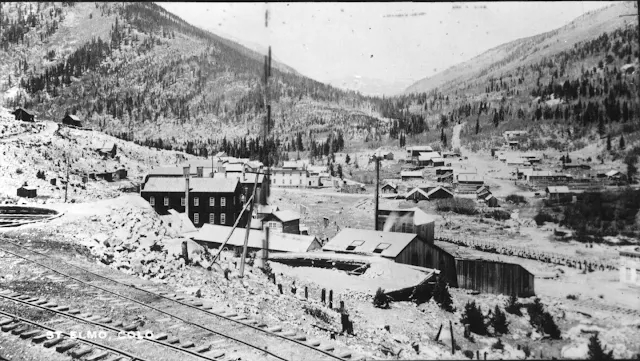

Crop from the photo, Post 32. This tipple appears to be at the upper end of the tramway built from level 4 to the eastern end of the works at Morley (Romley) in 1883. The elevation at the tipple appears to be generally 11,800' Above Sea Level (ASL). The Mary Murphy mine head was over the ridge to the left and about 400 ' higher. The photo was taken from a quarter of a mile away, near the level 14 tunnel. 1983 - Poole Photo

The primary ridge of Chrysolite Mountain runs about 25 degrees to the north east from the peak.(12,831 ASL, Google Earth). A secondary ridge slopes away from the peak approximately 50 degrees to the north west. Below this ridge is a small, poorly defined cirque and 100 feet below are the remains of the Mary Murphy mine head. Tailing from the mine's initial adit (Tunnel 100) sprawl down the slope on the east side of the structure. The elevation at the mine head is about 12,230 feet ASL The distance from the peak to the mine is approx 2,125 feet.

There were many mines, numerous veins and dozens of claims within the Mary Murphy complex. Of course, it didn't start as a complex. The original "Mary Murphy Claim" was 300 feet wide and 1500 feet long. It extended from the south western face of Chrysolite, went over the ridge above the mine and northerly toward Chalk Creek. Among the oldest claims were the Old Discovery, the Mary Murphy, the Livingstone, the Mollie, and the Iron Chest. The mines included the Mary Murphy, the Iron Chest (Pat Murphy?) and the Raras Warrior. The primary Veins included the Mary Murphy, three Pat Murphys (Pat, West Pat and East Pat) as well as the Jim Crow Lode and the Western; there were many more. All of the veins in Chrysolite were intrusive deposits of Pyretic Quartz. The vein gangue is a vuggie quartz and all of this is part of the Mount Princeton Batholith, a formation of quartz monzonite (granite) from the Cenozoic Era.

The main tunnels of the complex were at the 400',700', 900' and1400' levels. There were many secondary tunnels and adits to the main tunnels. There were numerous sub-levels, drifts, raises (shafts between levels) and ore chutes. Many of the veins were accessed only from within the interior network. Below all of this, the Golf Tunnel connected to Tunnel (Level) 14 by a shaft of 800 feet. The Golf Tunnel was built in 1911 at 2200 feet below the benchmark ridge above the Mary's mine head. The Golf Tunnel was 5800* feet in length from the entrance at the Golf Mill to the Mary Murphy Lode and its connection to the 14th Level. The Tunnel was wide enough for two parallel narrow tracks of perhaps 2 foot gauge or less. The ore trains were electrified.

[*This length of 5800 feet, is difficult to prove on modern satellite imaging. Measured as a straight line it is 4800 feet from the Golf Mill to the Mary Murphy mine head; an interesting figure! The Tunnel enters the westerly boundary of the Mary Murphy Claim 100' south of the Claim's northern most corner. It continues on this straight course into the claim at an angle, for another 300(+) feet. Then it angles to the right about 100 degrees. Within this course the Tunnel wanders another 800 or so feet until it reached the raise to Level 14(1400). This may account for the "lost" 1000 feet given in the Report.]

In the Chalk Creek district, the Mary Murphy was legendary. When its prime production period came to an end in the 1920s, it may have produced as much as $60 million in metals. The recorded amount was $14 million but in a day when $100 was a fortune to most Americans (when you could buy an ounce of gold for $32) either figure is unfathomable. However, each figure may be correct within context. If the lesser amount was in terms of profit, a LOT of money was invested into the property over the years. During the earlier development period (1880s and '90s?) the Mary Murphy Mining Company was actively purchasing mines and claims; not to mention digging tunnels and aggressively building and improving processing facilities. The $60 million may be correct in terms of gross production.

Who discovered the mine and when? And why was it named "Mary Murphy"? The story, as published by the Denver Post (11 Dec. 1913), is that the man who discovered the mine named it after a nurse who had brought him back to health during an illness. In gratitude, he named the mine for her. How romantic! It is generally accepted that John Royal discovered the mine in 1875. Yet, while there is plenty of narrative about Royal, who reportedly did a lot of "narrative" himself, there seems no mention of any woman nor explanation of the naming of the mine associated with him. Notwithstanding, legends often do possess a basis of truth.There are other stories that may hold more credence; between the mid 1980s and early 2000s, I visited the Colorado Historical Society (CHS) many times (Western History Department of the Denver Public Library). I accumulated an abundance of notes by good old fashion pencil on paper. (The curator was always reluctant to expose the old documents to "modern" copying technology.) In reviewing those notes, I was reminded of an account from the 1870's by an unnamed man who claimed to have discovered the Mary Murphy in 1870. He later took on partners willing to invest in the mine. For whatever reason he was absent for a period of time and when he returned they had usurped his ownership and shut him out of the property. This first person account was quite bitter

Found with this account in the CHS file box, there was a copy of the comprehensive book, "The Charisma of Chalk Creek" by Stella H. Bailey, (1985). Within this limited edition volume was a report that is described as a common understanding of the locals of Chalk Creek. The author was told by Harry Bender (page 89) that the Mary Murphy was discovered in 1870 by a married couple named Murphy. The wife was named Mary. They worked the mine with a horse and a scoop shovel. The man named the mine after his wife. (One wonders if his name might have been "Pat"?)

None of these stories particularly exclude any of the others nor the essence of the romanticism. By conjecture only, Mary the wife, could have also been Mary the nurse; whether she was both when she nursed the man back to health or not. Moreover, the date of the Murphy discovery appears to coincides with Geological Survey Professional Paper 289, U.S. Dept. of the Interior, 1957, which found that the mine had operated continuously since 1870.

|

| An unfortunately poor exposure of the structures at the Level 14 Tunnel. (Perhaps a future Post will discuss the various cameras I have used over the years) 1983 - Poole Photo |

John Royal and Dr. Abner Wright came into possession of the mine in 1875. Did they discover the mine? Did they rediscover it? Did they buy it? Did they assume it was abandoned and took it? Dr.Wright in particular, seemed of an honorable character; being educated, a Civil War Veteran and something of a local politician. John Royal was a bit less esteemed. Royal and Wright sold the mine to Chapman and Riggins. They were prominent figures of the town of Alpine, 6 1/2 miles down the valley from what would become Romley. In 1880, Chapman and Riggins sold the Mary Murphy to a St. Louis firm for $100,000. The new owners formed the Mary Murphy Mining Company (MMMC) with headquarters in St. Louis, MO. The principles of the company were; president James H. Morley; V.P. William P. Donaldson; Secretary / Treasurer J. H. Billings; General Manager Col. John H. Kelley; and Engineer F. T. Werlitz (of St. Elmo).

It was the MMMC that expanded the complex; by gathering up many of the independent mines in Pomeroy Gulch, digging nearly all of the tunnel down to level 14 (inclusive) and building most of the improvements at and to Romley.