-

|

| Balance; this HO Pacific (Key Imports A.T.&S.F. 1226) is about to undergo a balancing act |

Several years ago a client sent a P-B-L, S scale, narrow gauge K-36; similar to the model shown below. Among other cosmetic repairs he complained that the model did not pull well. His layout included a 2 percent grade helix where the model could only pull 8 freight cars to the top. This was disappointing as the K classes were the largest locomotives on D.& R.G.W.narrow gauge and to this day they pull longer trains of similar cars up steeper grades on the Durango & Silverton R.R.

The model did not meet his expectations. He had several of the 480 class big mikes and it is assumed they all did better than his 486.

The issue of model traction is a subject that I've studied for many years. On my Sn3 C&S layout I discovered that the small moguls and consolidations were unable to pull even a single brass passenger car up hill from Hess to Bath. Swallowing my own disappointment I defiantly decided I would come to a better conclusion than to just set those models on a shelf - as it seemed Overland thought little more of their product than that. I had several intertwining ideas about what to do but after the K-36 I began to realize a more deliberate approach to the problem. Unfortunately, I don't have the layout anymore nor do I have time to work my models. Instead I've set out to enhance our services to the benefit of our clients at 7th Street Shops.

|

| Even this finely crafted P-B-L K-36 is subject to physics |

Let's examine the issue a little closer. When a model doesn't pull well it seems the common assumption is that it lacks sufficient weight. But my experiences show time and again simply adding weight is more like trying to pour a gallon of water into a 1 quart jar. When more weight is added to say, a four axle coupling and only 1 axle is actually pulling, adding weight is a waste and the issue is not addressed.

Most manufacturers add ample weight to their models. Adding more weight starts to burden the power train (motor, gears and mechanism). Too much weight increases wear on these parts and they may prematurely fail. The reality is that simply adding weight to a poor puller is likely not the correct answer.

The fundamental problem is that of floating drivers whereby one or more axles do not sufficiantly press their wheels onto the rail tops. Two factors cause floating drivers; incorrect springs and a driver coupling that is not properly balance. For this reason it should go without saying that this topic is generally exclusive to side rod steam locomotives. In other words, these issues rarely effects sidewinders, diesels and other models that depend upon powered or shafted trucks rather than reciprocating drivers.

We will discuss springs at another time (springs, not suspension). True driver coupling suspension is rarely found on production models).

You have to be pretty dedicated to properly determine the specifics of an imbalanced driver coupling. The determination process is a bit tedious but the real impediment is the availability of the tools required to investigate the state of balance.You cannot fix what you can't determine needs fixing.

You likely have noticed a few of my tools in the photos shared here. The beam seen in the title photo didn't come by UPS. It came out of our machine shop. Nor did it just happen. When I started I did not know what features it would need. This beam is the result of a developmental process. When I tested Patrick's K-36 I temporarily fastened a small diameter rod to the table top and attempted to balance a plate/beam over it. This arrangement was difficult to manage because it was very easy to move the plate and or rocker rod when the engine was set upon the plate. But I persisted and until I could determine that the engine was out of balance and which direction it was too heavy.

|

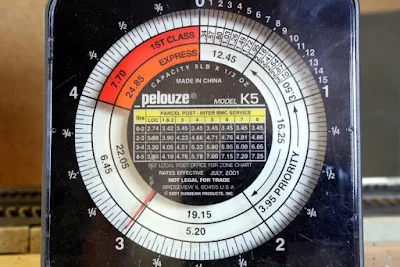

The second tool is a scale with some degree of accuracy. I already had a postal scale. While it can't be relied upon for gun powder accuracy or exact postage due for shipping it does quite well for this purpose.

There must also be some type of weighting material that offers both flexibility and the ability to attach it to the model. I have a box full of lead pieces that I use for this purpose. You will need material to be used to make the corrections permanent as well.

I've mentioned our machine shop. The ability to make boiler weights is often a valuable asset. Of course, the average modeler may only have an occasional need to do this but when many models come thru the door - all in needing some type of attention - the need becomes apparent.

The last "tools" are more abstract; that of knowledge. I'm sure there is a cadre of experts out there (there always are) with this knowledge (which is why we see so much published on the matter) but frankly, very little is readily available and at times, what I see suggests that this knowledge is generally far from the average modelers purview. What I've learned is from hard earned experience and a few

bits and pieces from old magazine that offered hints along the way.

I'll finish this post by sharing the rest of the story of my client's K-36. This will be enlightening.

I determined the model had come from the factory out of balance; there was no indication of any modifications. The boiler weight was soldered to the shell per usual so actually removing it would be very difficult. Therefore I cut away material where it was excessive and added weight until the model balanced on the makeshift beam. This attained the goal of equal pressure of all 8 drivers on the rails. What ever a steam locomotive can do with what ever weight available to it, equal pressure will maximize its tractive effort to that measure. This is the reason cramming lead into every nook and cranny is not usually necessary.

I returned the model to the client and when we talked on the phone some days later this is what he told me; "I don't know what you did to this model but where it could only pull 8 narrow gauge freight cars (in S scale they are roughly the same actual size as an HO 40' standard gauge car) it can now pull 18 cars up the same 2 percent grade on a curve!"

The

K-36 experience has not been unique. With the proper tools and working knowledge the results are consistently that direct. After balancing the Sante Fe

engine in the title photo above it is capable of pulling 12, 40' freight

cars - 42oz (each weighing 3.5 oz) - up a 2 percent grade. The weight in the model was not increased or decreased from the factory; merely redistributed. The engine, itself a medium size, only weighs 13oz. The tender weighs 6 oz and is in addition to the 42oz. The effective pulling is determined at the point just before the drivers begin to slip. With slipping it can pull a few more cars.

|

| HO (40' box) and Sn3 (30' box) cars are roughly the same size (6" L x 1.5" W x 2" H @ 3.5oz ea.) |

We will continue this discussion in a future post.

I totally agree with you that model engines should be balanced. As a fellow builder for 44+ years now, I've always have strived to make any model look it's best and operate the best that I could. Why not take the extra steps to make sure the model (in any scale) performs it's best as well with doing what it was designed for~ pulling. I like the clear thought process you explain and have even taken some of the same actions in trying to make my engines push and pull equally from both ends. I look forward to your next postings. Very good stuff here.

ReplyDeleteThanx Thom...

Thanks Thom. With the balance beam finally operational 7th Street Shops has pretty much incorporated balance into the general service package of a model when it comes with power train issues and or upgrades. Vital. I've had models that couldn't hardly pull themselves - the HOn3 Mason Bogies of the late '60s for instance. Marvelous models of a prototype that really wasn't much better than the models. Which is why most of the South Park bogies became stationary steam engines in machine shops and pump houses.

Delete